This Indian Origin US Doctor's Method Can Quickly Help Millions In Need Of Eye Transplants

Eye transplants don't happen very often. One reason is that not a lot of people put themselves on a donor list before they die. Another is that eyes from a patient that's died of old age usually aren't the best option. But what if we print our own?

Eye transplants don't happen very often. One reason is that not a lot of people put themselves on a donor list before they die.

Another is that eyes from a patient that's died of old age usually aren't the best option. That's why this team of medical professionals wants to make their own.

Tori Schneider/Tallahassee Democrat

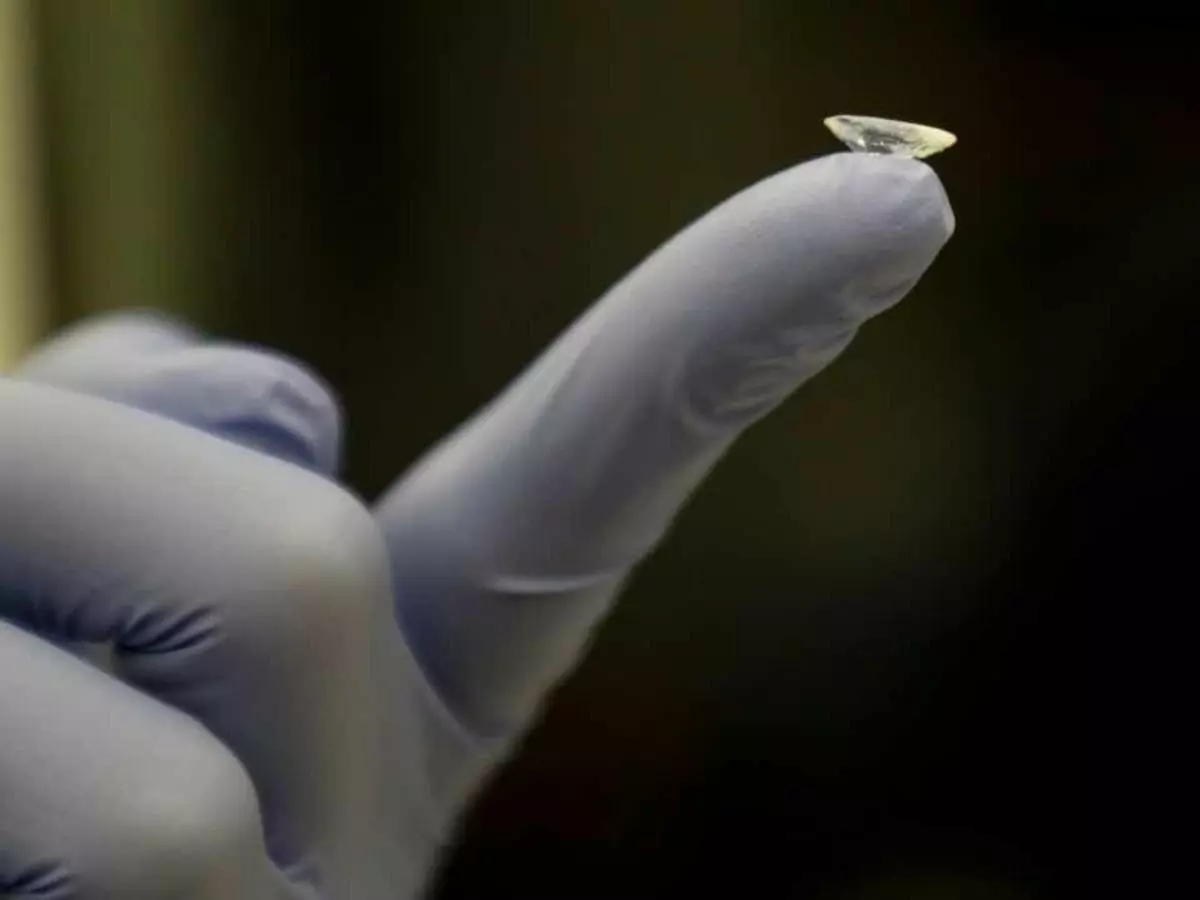

A team of researchers from Florida A&M University Pharmaceutics have just succeeded in fabricating a high throughput 3D print of a cornea. Led by Professor Mandip Sachdeva, the project could make for huge advances in the medical field. Not just as an added supply for transplants, they could also be used to test new methods to treat wounded corneas.

Sachdeva, along with Shallu Kutlehria, a graduate assistant in the College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, and research assistant Paul Dinh, are publishing a white paper on the topic in a journal later this month.

The breakthrough comes as part of a research grant Sachdeva received in 2017 for research that could be used in bioprinting, aerospace materials, and energy. He's not the first to 3D print a cornea, that honour goes to scientists at Newcastle University in the UK last year. His cornea work though focuses on how to print them at a much faster rate.

"Essentially, the idea was, 'Can we do something better than this?" he said. "Can we simulate the human eye, and put a cornea with cells in it?'"

FAMU

Sachdeva describes how, in the UK study, the printing of a single cornea took a long time. That's all well and good for a proof of concept, but it's not scalable. Using his team's method however, they were able to print six corneas in just 10 minutes.

The most obvious application for this research will be for transplants. However, the team also believe it can be used to research how to improve the permeation of ocular drugs and formulations, as well as how to screen corneas for aberrations.