A Remote Villager Is Using His Art To Revive The Dying Art Of Arabic Calligraphy

Hailing from a remote village in Telangana and currently based in Bengaluru, Muqtar is on a mission to revive this dying art in India.

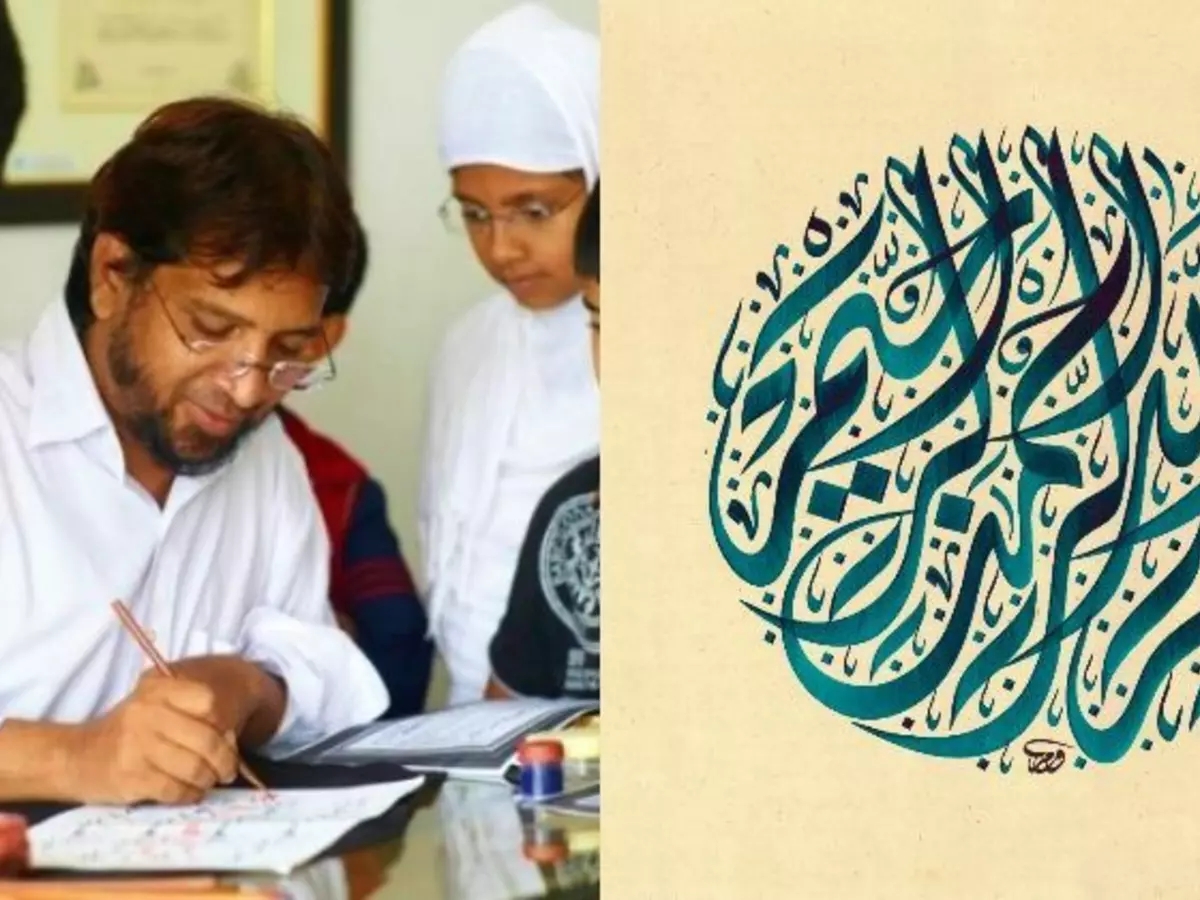

Arabic calligraphy is worship for Muqtar Ahmed, an Indian calligrapher who has made a mark for himself at the international level. Hailing from a remote village in Telangana and currently based in Bengaluru, Muqtar is on a mission to revive this dying art in India.

As beautiful as pearls, his works attract the attention even if one is not familiar with the Arabic language. According to Ahmed, the aesthetics and refinement are the specialities of Islamic art.

"Writing the Quranic verses and Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Mohammad) is worship. These works are sawab-e-jaria (continuous reward)," the calligrapher, who believes that there is no script more beautiful in the world, told IANS.

Muqtar believes his efforts have started yielding results as his disciples are carving a niche for themselves at the global level.

The only Indian to obtain an "Ijazah" (Master's diploma) from the Istanbul-based Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA) of the Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation (OIC), Muqtar is grooming young talent at the Institute of Indo-Islamic Art and Culture (IIIAC) in Bengaluru.

He has so far trained 500 youngsters, including students, professionals and others coming from varied backgrounds at the institute. A Japanese girl is among the three foreigners who learnt Arabic calligraphy under him.

Muqtar, whose calligraphic works adorn mosques and even private jets abroad, is happy that the institute is getting global recognition for the high standards set by it in Arabic calligraphy.

Three of those trained under Muqtar bagged the top prizes at a national-level calligraphy competition organised in New Delhi last year by Yayasan Restu, a Malaysian organisation. Ameerul Islam and Abdul Sattar of Hyderabad won the top honours.

They were selected for an 18-month training programme in Malaysia.

About 400 people from calligraphy institutes across the country participated in the competition. "For the first time, people in India saw what real Arabic calligraphy is," said Muqtar, who has participated in many exhibitions in different parts of the world.

According to him, the art in India has been in continuous decline after the end of Mughal rule. He pointed out that the calligraphy work in India was never recognised globally as it was nowhere near the international standard.

Representational Image

Ameerul Islam and Abdul Sattar are now teaching calligraphy at the institute's Hyderabad branch, which was opened recently. The talented youth, who have participated in competitions in various countries, is training more than 20 students.

Muqtar, who plans to open another branch of the institute in Lucknow, believes that with more youngsters evincing interest in Arabic calligraphy, the art has bright future in the country.

The "ijazah" obtained by Muqtar in 2013 may have fetched him a good job in the Arab world, where Islamic art is greatly valued. But he stayed back to revive the art in India, where it once enjoyed royal patronage.

Syed Mohammed Beary, chairman, Bearys Group of Companies, came forward to help him in his mission by setting up IIIAC.

One of the works of 50-year-old Muqtar, settled in Bengaluru for nearly three decades, was purchased by the then governor of Madina in 2011 when he participated in the international exhibition in the holy city in Saudi Arabia.

Interested in calligraphy from his school days, Muqtar migrated from his village in Medak district to Hyderabad to learn the art. He them moved to Bengaluru where he started working for a Urdu daily.

Representational Image

Rendered jobless after the newspaper replaced calligraphy with computers in the early 1990s, Muqtar started writing wedding cards to make a living. "It was not my goal. I wanted to go deep into the art," recalled the artist who improved his art under renowned international calligraphers Mamoun Luthfi Sakkal and Mohammed Zakariya of the US, and refined it further under the guidance of Turkey's Hassan Chalabi and Dawood Biktash.

Muqtar, who uses special, hand-made pens for his writings, said he achieved precision with perseverance. "Even a small piece of calligraphy takes several hours. You have to write a letter hundreds of times to achieve accuracy," he said.