This AI Can Tell Good Eggs From Bad, And Could Save IVF Women A Lot Of Money Very Soon

Many women these days decide to freeze their eggs so they can postpone trying for kids at a later stage. Currently, it¡¯s estimated that only a third of all frozen eggs result in successful pregnancies. That¡¯s where this startup comes in.

Thanks to job saturation and other factors, it's harder for millennials to advance your career than previous generations.

To that end, many women these days decide to freeze their eggs so they can postpone trying for kids at a later stage. However, there's no guarantee how fertile they are.

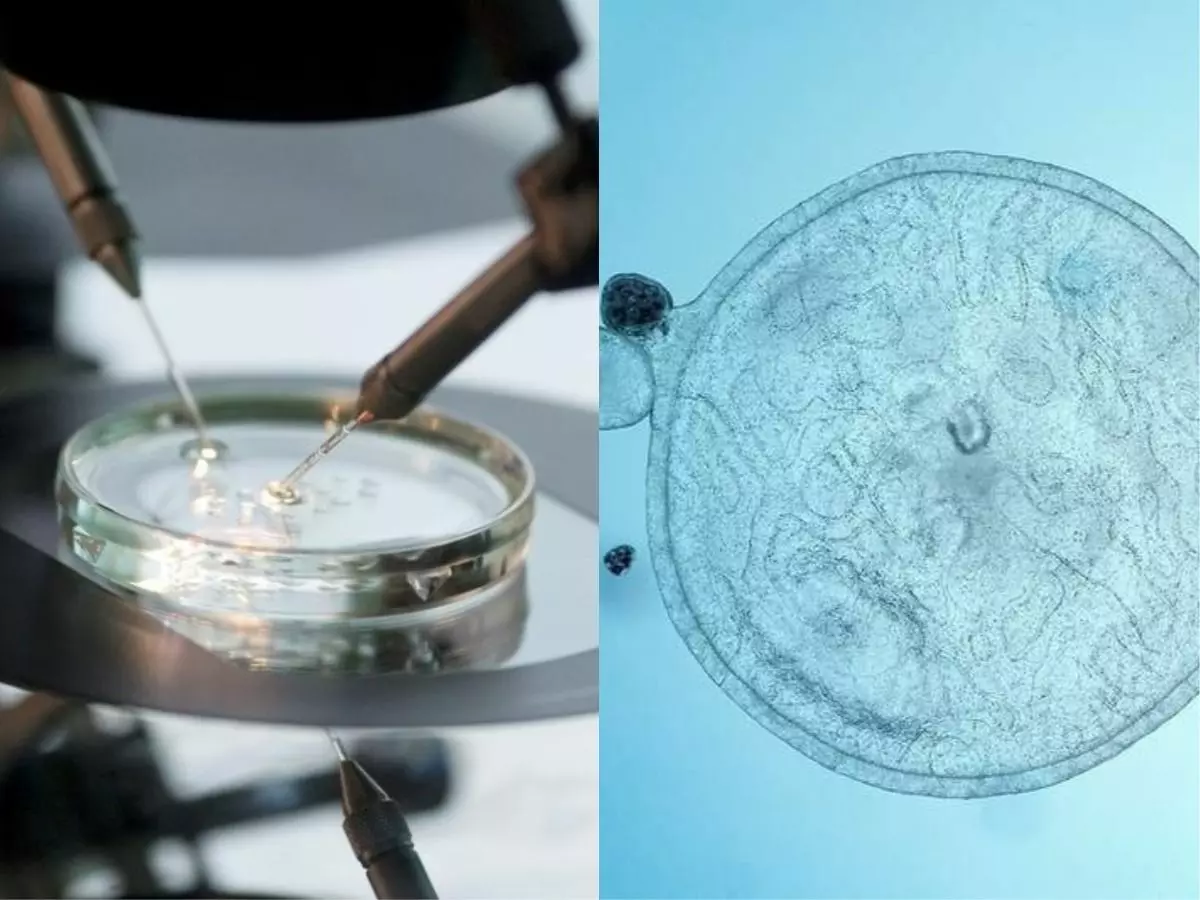

This means that, when these women have their eggs unfrozen years later and attempt to use them to conceive (usually, through IVF) there's a chance they'll fail. That's worse if the woman is past her prime and her ovaries aren't as fertile as they used to be to produce more. Currently, it's estimated that only a third of all frozen eggs result in successful pregnancies. That's where this startup comes in.

Future Fertility wants to fix the problem using AI, of course. The current method for this whole process involves a really old system fromthe 19th century. Fertility doctors match a woman's age with the number of eggs they've retrieved from her at the time of freezing. Then, based on historical averages, they can give her an estimate of what her chances are of getting pregnant with them. Of course, this isn't the most accurate method.

Canada-based Future Fertility however has developed what it calls a full-automated egg-scoring algorithm. The neural network, named Violet, can supposedly predict successful pregnancies from the frozen eggs with a 90 percent accuracy, and that's using only a single microscopic scan.

There are limits however. Violet only has a 65 percent accuracy when predicting whether the embryo will then survive more than five days, and it's even less accurate when predicting whether it will survive being implanted in the woman's uterus. However, the company insists those stats will get better as IVF clinics begin using the AI and it gleans more data it can learn from.

"To me it was always the craziest thing that we have some sort of classification for sperm, for embryos, for the inner lining of the uterus, but I can never give patients any feedback for eggs," Dan Nayot, medical director at Future Fertility, told Wired. "To the human eye, eggs just look pretty similar. At this point it's sort of a coin toss."

Violet was trained on 20,000 images anonymous health records from a number of partner IVF clinics in Canada. It'll now begin testing in a number of clinics, both in Canada and in other countries like the US, Japan, and Spain.

If the results continue to be promising, this could be the biggest advance for IVF in years. For one thing, it means couples don't have to wait for the entire IVF process to see if they're going to be successful. Instead they can get a better idea the minute the doctor retrieves eggs, meaning they waste less time and money on the later stages of the procedure. And it requires barely any new hardware for clinics, just a camera and new software to go with it.